The yin and yang of user-centric bio hacks

German philosopher Heidegger had not witnessed the use of technology to create addictive tools like the social media in his time. Nor had he witnessed the use of technology to make environmentally friendly solutions like the electric automobile. And yet, he went on to say that modern technology takes us away from the true essence of objects and makes everything into resources. He explained that when a tree is simply seen as a tree, we are closer to acknowledging its true essence, i.e. there is at least a possibility of knowing it for what it is. But when we use a tree as a technology to make paper and large ships, the tree is merely a resource and we lose our understanding of its true nature. Now, say we infuse our human bodies with technology through the means of biohacking, does this mean that humans will no longer be seen as humans but as mere resources for data to better understand the human body?

We don’t know yet.

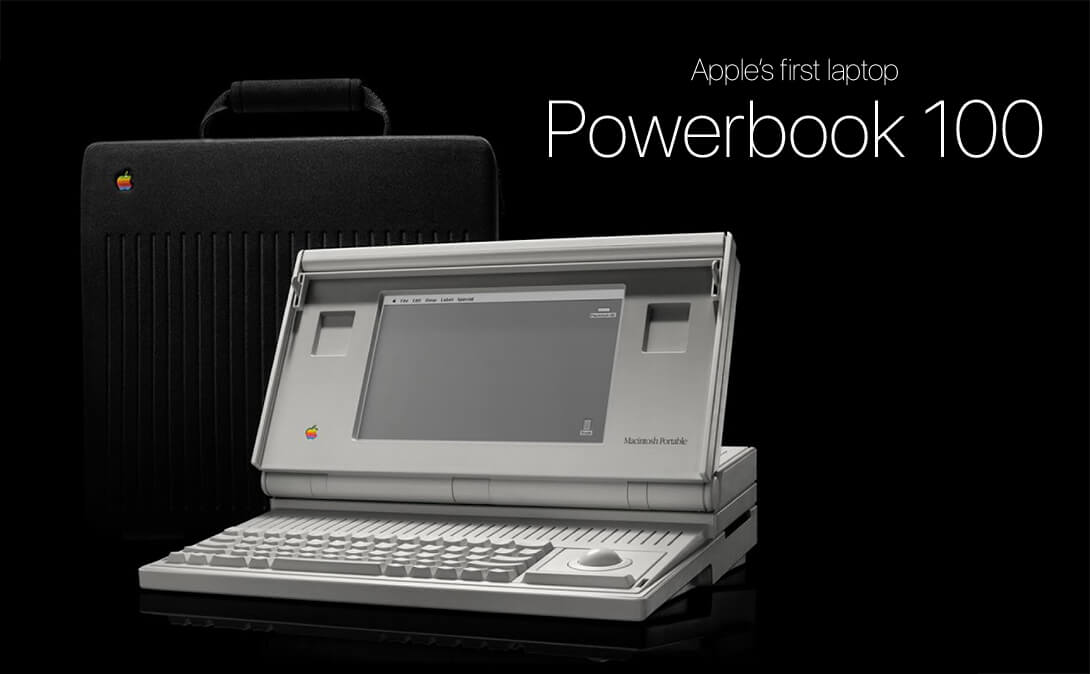

The UNIVAC-1, commonly known as the first commercial computer to have received widespread public attention, was sold at a cost of $1 million each in 1951. Forty years later in 1991, Apple sold its first laptop – the Powerbook 100 at the cost of $2500 and made the technology accessible to individual users. In essence, direct-to-consumer genetic kits have made genetic science more accessible to the general public. Customers are able to share their DNA samples with test providers and receive detailed reports on their ancestry and critical health information such as whether one is susceptible to early baldness or even a certain kind of cancer.

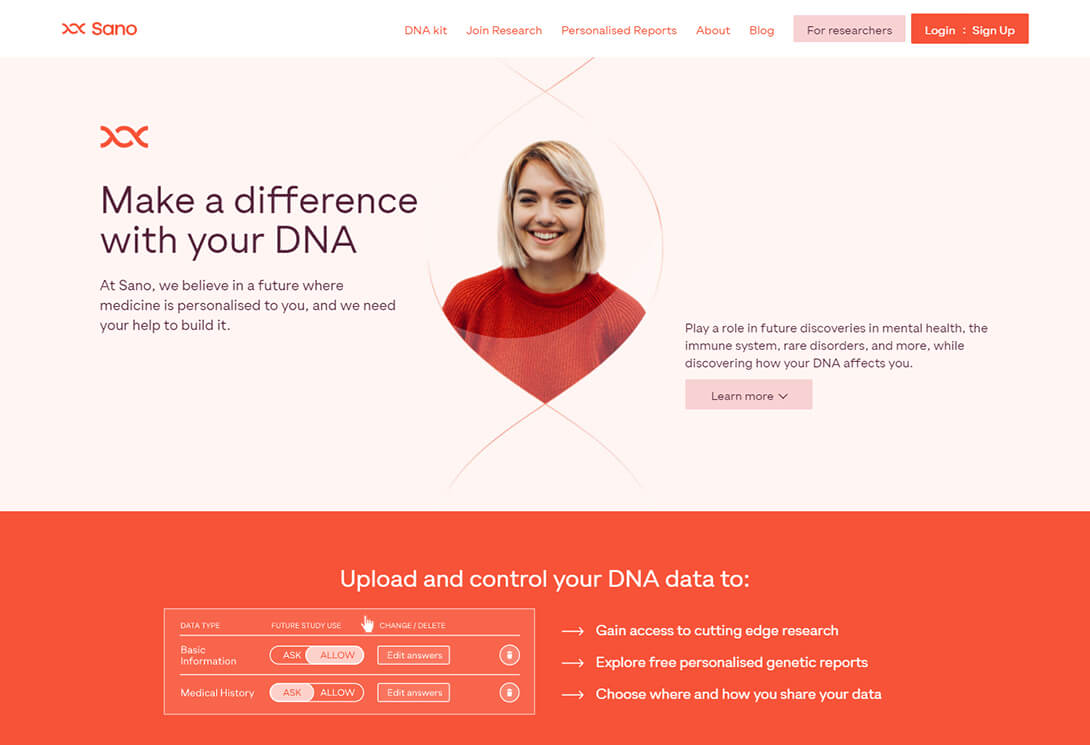

Japanese brand MYCODE collaborated with design innovation company IDEO to engage customers in this new territory of consumer genetics. Right from the moment a customer requests a test to receiving results in humane, compassionate ways, MYCODE has been appreciated for delivering high levels of service with the strongest adherence to ethics. Similarly, a UK gene-testing company Sano Genetics has tactfully used the colour orange to make the approach to healthcare friendly. You can sign-up to their newsletter that delivers complex biological information in very easy-to-understand blogs. Such UX techniques are seamlessly opening up avenues of science and technology that were once restricted to certified professionals in the confinement of labs.

Speaking the language of the consumer goes beyond branding essentials like the name, logo and visual identity. The brand 23andMe worked closely with a design agency to deep-dive into the company’s goals and its customer’s needs. The outcome is a product that encourages users to take active steps towards bettering their health. Tools like customised notifications, user-specific information and access to specialists makes it easier for users to allow this new technology into their lives. Some also engage social media platforms to create a sense of genetic kinship and virtual community.

The consumerization of genomics began early in the 1990s when University Diagnostics, a start-up firm in the UK began a mail-order service of gene-testing kits. But consumer genetics kit took on a whole new meaning when in 2017, scientist, bio-hacker and social activist Josiah Zayner injected himself with CRISPR to alter his DNA to enhance his muscles – live on camera. His company The ODIN sells CRISPR kits to empower the people with life-changing technology that he says is widely known by professionals but is not made available to the general public. In that same year, an experiment noted that receiving concerning news about one’s health from these gene tests lead to high levels of discomfort among certain test takers, which can actually prove to be detrimental to people’s mental health.

So, you see, the space is highly contested with polar opposite views. While some members of the science, technology and creative communities look upon this ‘massification’ of genetics as an impending genetics revolution – futurist Jamie Metzl, PhD has written a book called Hacking Darwin: Genetic Engineering and the Future of Humanity – there are others that are deeply concerned about the fake hope this may give people and the ethical questions of tinkering with one’s genes in unregulated conditions. In 2018, when a scientist in China successfully delivered CRISPR babies there was extreme discomfort from the fact that this could soon revive the eugenics revolution. Even before the Nazis partook in careful elimination of a race that they considered inferior to them, in the early twentieth century, the Compulsory Sterilisation law was already being practised in 30 states in the United States!

An on-going debate between realists and revolutionaries, the polarisation of opinions on technology breakthroughs has existed throughout history. In 1958, when the first person was implanted with a pacemaker, he went on to live for another 43 years but when this technology was first made public in the 1920s, it was not well received, being called a technology that revives the dead. Similarly, implants like magnet and bluetooth teeth do have a small audience but it is mostly done by ‘garage surgeons’ like Jeffrey Tibbitts. There are certainly some success stories like that of Neil Harbisson, a man born colour blind who got an antenna implanted on his head such that he can now ‘hear’ colour.

This debate brings us back to Heidegger’s concerns about modern technology. It’ll be ironic if we have the most user sensitive and immersive direct-to-consumer genetic kits, but the users become mere resources to collect data and experiment on. In spite of deliberate efforts to tactfully engage users in the field of genomics with mobile apps, a study showed that though the apps are generally of high quality in terms of resources available, they still need to be improved from a credibility and ethics point-of-view. Only time will reveal the complete impact of user-driven biotech.

Writing credit – Vishanka